Why was a world-class composer still installing dishwashers in his forties?

Why some people can't change their spots (and it's not about habits)

The late art critic Robert Hughes once arrived back at his Manhattan loft to check on how his new dishwasher installation was going. The plumber was on his knees, sleeves rolled up, head inside the machine.

When he eventually looked up. Hughes stared at him goggle-eyed and aghast.

"My god – you’re Philip Glass. I can’t believe it! What are you doing here?"

Glass, by then already one of the most important composers alive, answered flatly: "It’s obvious, isn’t it? I’m installing your dishwasher."

Hughes, still baffled, protested. "But… you’re an ARTIST!”

Glass replied, "Yes, I’m an artist, but I’m sometimes a plumber as well – so can you please just leave me alone and let me finish what I’m doing?"

This one absurd scene says more about how change actually works (and why it usually doesn’t go quite the way we plan it) than 99% of the advice being peddled online.

Glass wasn’t just doing a bit of side work while waiting for his big break. His break had already happened. He was composing, performing, being commissioned, lauded, recognised. And yet, well into his forties, he was still driving a cab, moving furniture, and doing plumbing odd jobs.

It wasn’t because he lacked talent, or because he was lazy, or because he was a late bloomer.

He stayed trapped because somewhere deep in his system, the unconscious story he was living in hadn’t yet updated. The wiring he’d absorbed growing up – working-class, immigrant, survival-focused – still told him:

Only “real work” pays the bills.

Real work is the only thing you can count on.

Art is something on the side. Not to be trusted.

Even as his career took off, that older script ran beneath the surface, quietly controlling his decisions.

And when he finally allowed himself to change, to give up driving his cab and doing odd jobs – it wasn’t discipline or habits that finally shifted the story. It was his entire system gradually allowing itself to trust that this not-so-new version of his life was safe.

Most people don’t realise that this is how change actually happens.

Which is why so much of what gets packaged up and sold to us as "personal development advice" is, quite frankly, absolute nonsense.

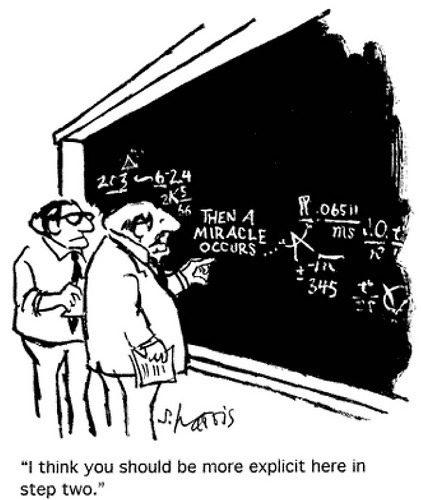

Spend five minutes on Substack or LinkedIn and you’ll drown in it. The endless parade of well-meaning people explaining that the problem is your habits, your routine, your lack of discipline, your lack of consistency. If only you were 1% better every day. If only you optimised your morning routine. If only you fixed your mindset.

As if the reason Philip Glass was still driving a cab at the age of 42 was because he hadn’t read Atomic Habits.

This is the fantasy most self-help content is built on: that people are stuck because they lack tools, strategies, or information. That change is a matter of applying the right framework. That your willpower just needs a better system.

But for most of us, and certainly for the people I work with, that’s not the problem at all.

The problem is that the system that controls your behaviour is almost entirely unconscious.

You can stack all the habits you like, but if your nervous system believes that artists never make money, that self-employment is dangerous, that saying no equals rejection, or that visibility will lead to punishment, you will keep circling back to the same old patterns that keep you stuck.

The system always wins.

And I know, because I’ve lived it.

I grew up inside my own version of Glass’s survival script. My father went to work every day and resented every minute of it. My mother actively resisted work altogether. Between them, I absorbed two messages at once: work is miserable torture but necessary for financial security, and work is soul-sapping and should be avoided at all costs. The conclusion I drew was simple: you don’t get to enjoy work. You endure it, because that’s what grown-ups do.

What I didn’t realise then was that this wasn’t just a belief. It was a survival strategy. Like many people carrying complex PTSD, I had learned to stay safe by constantly scanning for danger, anticipating other people’s moods, avoiding conflict, and trying to control my environment wherever I could.

Which is why, without consciously intending to, as an adult I ended up being repeatedly drawn into workplaces that mirrored those early dynamics – places where control, volatility, humiliation, and hypervigilance were baked into the culture. My nervous system recognised them as familiar. They felt horrible, but they also felt weirdly normal. Because on some level, they were.

At the same time, I kept circling my desire for something different: something better, something more meaningful. I studied change obsessively. I did a PhD at Cambridge (or nearly did – I never finished, having crashed headfirst into my first neurodivergent wall… not that I figured that out for another couple of decades). I studied how stories can change belief systems. I built a career around behaviour change, motivation and persuasion: advertising, then digital innovation, then consulting, then coaching.

But while I was busy trying to understand change on paper, my nervous system kept pulling me back into environments that felt uncomfortably familiar. On paper, everything looked successful. Behind the scenes, I kept ending up inside exactly the kinds of toxic workplaces that reinforced the same old scripts, feelings and patterns.

One CEO I endured for a few years invented a form of torture he hilariously called "salons." They were positioned as our agency’s answer to TED Talks — glossy client-facing events where staff would present slick, cutting-edge work to impress the room. These salons were his personal pet project, and he controlled them with sadistic fervour.

He handpicked who got to speak. These unlucky employees would have to take their presentations to him first, behind closed doors, where he dismantled them slide by slide. People would walk into his office already jittery, usually having not slept a wink for weeks whilst they nervously polished and tweaked their ideas. They’d leave pale, hollowed out, on the verge of tears. The goal wasn’t high standards. It was control. The objective was breaking people long before they stood on stage.

The one time I presented to him (thankfully not for a “salon”, but to take him through the results of months of work on a major project), he sat through the whole deck in silence. At the end, his only feedback was: "I don’t like triangles." When I asked if there was anything else, he thought for a moment and added: "I don’t like circles either."

That was getting off lightly, indeed.

It wasn’t the first time I’d worked for people like this, and unfortunately it wasn’t the last. It was just one more loop in the same pattern. Toxic environments didn’t repel me – they felt familiar. I was trauma-bonded to the sort of system I’d grown up in, and my nervous system kept pulling me back to places that mirrored the original tension: power, control, humiliation, shame, survival.

I wasn’t failing to change my life because I lacked motivation. I kept failing to improve my lot because my system wouldn’t allow the change.

That’s what survival scripts do.

And this is where most advice completely falls apart. Because when you’re trapped in a hard-wired survival system, superficial behaviour-level change doesn’t touch it. Your prefrontal cortex might think it wants change. But your nervous system doesn’t believe it’s safe. And guess which one has the final say?

No habit stack fixes that. No morning routine rewires that. No gratitude practice resolves that.

Change finally started for me when I stopped trying to override the system and started working directly with it. Learning how to regulate my nervous system so that freedom didn’t feel dangerous. Learning first to make conscious and then rewrite the narratives I’d inherited. Learning to dismantle all the injunctions, prohibitions, and drivers that had shaped my life since childhood.

This is what system-level work looks like:

Somatic work that allows your body to feel safe, and allows you to inhabit your body safely

Narrative work that reveals the stories you didn’t even know you were living

Transactional Analysis that surfaces the unconscious rules you’ve obeyed for decades

Neuroplasticity work that allows well-rehearsed patterns to be rewired – including psychedelic work that helps access material that talking alone can’t reach

It’s not about willpower. It isn’t about doing more. Rather, it’s about learning how to shift the system so you can finally do what you already know you want.

This is what I do now. I work with people (mostly over 40, some younger, some a lot older) who’ve built successful careers, tried the coaching, read the books, done the therapy, but know they’re still running the same internal operating system. They don’t need more information. They need an entirely different theory of change.

In fact, this is the question I open every first session with:

What’s your theory of change?

It stumps most people. Almost nobody has an answer.

Sometimes people mumble something about mindset, positive thinking, setting goals, having the right plan, trying harder. Occasionally they mention discipline or consistency. Sometimes they cite a book or a framework they’ve tried to follow.

But very few have ever seriously examined the deeper question:

What’s actually running my system, that sits outside of my awareness?

What keeps me circling, even when I think I know exactly what I want?

And until that question gets answered, most of the usual self-improvement advice – goals, habits, plans – amounts to rearranging the furniture while the entire house slowly sinks under subsidence.

If any of this sounds familiar and you‘re interested in working with me, please drop me an DM.

As Derek Sivers once said "if more information was all we needed, we'd all be billionaires with 6 packs"...

This is all very interesting. It's the first time I've got to the end of a "how to improve your job prospects" pitch.

I love the quotation about Philip Glass.

I have studied music all my life, along with a dozen other disciplines, I know the buzz of playing before an audience, and I learnt as a teenager but, like writers and dancers and artists, only a tiny proportion made a living doing the thing they love.

Having said this, when my mother married my father, she was a professional artist, earning more than he did by far, but it wasn't done for a woman to be the breadwinner.

My father was an artisan, and because I was a poor scholar, I was encouraged to follow him.

However, through talent, luck, and being in the right place at the right time, I landed the job of my dreams.

By the time I was 30, I had formed my own company and was living the dream.

But the dream turned sour, and so I became a writer – I published successful books, but still did the odd job, repairing washing machines, drawing architectural plans for builders, and developing properties, because books didn't pay all of the bills.

I'm over 80 now, I still have my business, and I still have my dream of publishing the rest of my short stories and my incredible adventures.....